When parrots go to school

In Jen Cunha’s world, the term “bird brain” is not an insult. Instead, it’s the most sincere way to compliment someone’s intelligence. A researcher affiliated with Northeastern University, Jen has good reasons for admiring the cognitive power of birds. She lives with parrots who love children’s books, zip through digital puzzles and games on their tablets, and make video calls all on their own. Her parrots are also the subjects of peer-reviewed scientific research.

Jen’s journey began in 2012 when she adopted Ellie, a baby Goffin’s cockatoo with strong opinions and a fiery spirit. “When she first came home, she hated me. It was awful,” Jen recalls. “She showed so many frustration behaviors. She had a really pained scream. She threw glass off the counters. It was chaos!”

Jen refused to give up on her angry little white parrot. To engage Ellie, she tried every strategy she could find: employing force-free training techniques, giving her plenty of toys and foraging opportunities, and helping her learn an array of tricks. “There are only so many tricks you can teach a bird. We ran out,” Jen says. “She learned lightning fast, and she seemed happier on the days when she learned new things.”

On one especially chaotic day, Jen decided to try something new. She held up some foam bath-toy letters and began giving Ellie a preschool lesson of sorts. “I grabbed the letter A and I grabbed an apple, and I grabbed the letter B and I grabbed a banana,” Jen says. “Then I gave her discrimination tasks: Which was the apple? Which was the banana? I thought maybe she’d have five letters in her head and that would be it — but she kept learning and learning and learning. She would wake up and race to her learning station. A week or so later, she reached up and kissed my cheek for the first time.”

From that day forward, their relationship took flight. Jen describes Ellie as a “little daughter who can’t speak and has feathers.” She says, “I love her so much. She’s not only one of my very best friends — she’s my collaborator. I can’t even imagine doing Earth without her.”

A kindergarten for parrots

Wild parrots live in flocks and enjoy rich social lives, and their life spans can last decades — sometimes more than 60 years. When kept alone as pets in cages, they can become bored, stressed, and downright destructive. Some engage in self-harming behaviors such as plucking out their own feathers.

“People think they’re easier than other pets, but the opposite is true,” Jen notes. “It’s so easy to put their bodies in a cage because they’re so small, but they have such big needs. They need a lot of intellectual engagement.”

Since the fateful day with the foam letters, Jen’s work with Ellie and her two other cockatoos (Isabelle, a rescued bird with an amputated foot, and Tillie, a red-vented cockatoo) has reached dizzying heights.

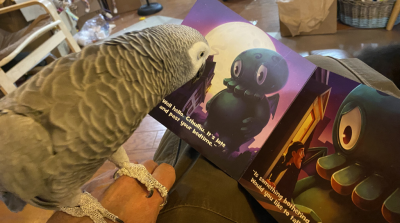

At their home in Jupiter, Florida, the birds pore over board books and deftly navigate tablet communication boards designed for nonverbal children. They use the tablets to tell Jen how they’re feeling, which activities they’d like to do, and where they’d like to do them.

Ellie has proven to be masterful at learning letters, blending letter sounds, and seeming to read about 300 words with genuine comprehension. She also can use her beak and tongue to draw 14 letters on her touch pad.

[Wallflower cockatoo blossoms into dancing king]

These strides in bird learning have been documented in academic papers and presented at scientific conferences. Jen is a real estate lawyer, but she has a bachelor’s degree in behavioral neuroscience and has co-authored seven research publications with scientists from Northeastern University, MIT, the University of Miami, the University of Glasgow, and other institutions.

Jen took her research work a step further when she launched Parrot Kindergarten in 2021. The online educational platform offers a series of five-minute lessons to help human caregivers engage with their parrots in new and rewarding ways. More than 200 parrots are enrolled in the program. “There are paid courses, but we offer a lot of free resources and workshops and training as well,” Jen says. “We really want this to be accessible to all learners.”

Time and again, Jen sees birds come to life with their caregivers when the birds are given the opportunity to learn and express themselves. This can be particularly powerful to witness in birds with histories of abuse, who come to their new homes as empty shells, Jen says. “Then you start teaching the bird to play and interact and have words and communicate, and they become like little people who have feathers in the family.”

Beth and Jonathan Kessler, animal rescuers and volunteers with Mickaboo Companion Bird Rescue, are grateful Parrot Kindergarten participants. They’re amazed by how much the Parrot Kindergarten curriculum has improved the quality of life of their four parrots: Molly, Cookie, Lou Grey, and Little Lou. “It was so clear from the beginning that this was making their lives more engaging, and it also was giving them more agency,” Jonathan says.

Beth says their birds didn’t take to the tablet right away because it requires them to use their tongues or their feet on touch screens, movements that weren’t immediately intuitive for them. “But you can teach them a yes card and no card very quickly,” Beth explains. “That and the board books — they liked reading books with us right away.”

Jonathan and Beth have acquired a library of children’s books for their birds. Molly and Lou Grey especially love the books Grumpy Monkey and My Big Dog. During their story-time ritual, the birds identify different characters and objects on the pages with their beaks and answer comprehension questions about the stories. “There’s an anthropocentric view that we as humans are radically different from and superior to other species of animals,” Jonathan says. “This is really challenging that.”

The holy grail of communication

What is it about humans’ relationships with our pets — regardless of species — that can make us feel so invested in communicating with them? Jen sums up the answer in one word: love. She says, “We want to communicate with them because we love them. I remember looking at Ellie when she was a baby and seeing her fierce intelligence and realizing that she could live to be 65 or 70 years old. I wanted her to be able to tell me her preferences out of love.”

Our desire to communicate with our animals also is linked to our desire to give them the best possible care. Jen says, “We find ourselves thinking: What would give you a meaningful life? What would be good for you? I want you to have a good life and for you to be able to tell me what you want.”

Jen’s work with Ellie, Isabelle, and Tillie has revealed preferences and personality traits that she never would have anticipated. For instance, Ellie adores pumpkins and fall — it’s her favorite season. Ellie also has shown an unexpectedly tender side with her feathered siblings. When she senses that Isabelle or Tillie might be craving attention, she’ll hop onto her tablet and give Jen some pointed guidance: “Mom touch Isabelle.”

[This adopter’s home is for the birds — literally]

Two-way communication with the birds also has practical benefits. Jen provided them with a speech board on their tablet that includes the pictures and names of different body parts. “Isabelle kept using her tablet to say, ‘Tummy, ouch. Tummy, ouch. Tummy, ouch,’” Jen explains. “She had been to the vet pretty recently, and it’s extremely stressful to take her to the vet. But she kept saying it, so I took her back.”

It turned out that Isabelle had a staph infection. “The vet and I were shocked,” Jen says. “Isabelle looked fine, and she hadn’t lost any weight. I never would have known anything was wrong if she couldn’t tell me.”

Parrot Kindergarten has launched an interspecies workshop to see what other sorts of animals — from horses to guinea pigs to lizards to squirrels to ducks — might benefit from tablet communication boards, children’s books, and other learning and communication tools.

“My little fish, Libby, really likes books. Other animals really like to use the tablet. I’m not sure about snails. I haven’t explored snails yet,” Jen says with a laugh. “There’s just so much inside these animals that’s waiting to be expressed.”

Laura T. Coffey is a longtime journalist and author of My Old Dog: Rescued Pets with Remarkable Second Acts, which features beautiful photographs of senior dogs taken by Best Friends photographer Lori Fusaro.

Video chats with BFFs (best feathered friends)

Jen Cunha’s cockatoo, Ellie, operates her tablet like a digital native. She uses it to call Jen and Jen’s mom whenever she feels like it, and that’s not all. She also uses it to chat via video with her closest bird friends across the country.

Ellie was an eager participant in the efforts of scientific researchers to determine how parrots living in captivity might benefit from video-calling technology. Their study’s findings, which were released in April 2023, were drawn from more than 1,000 hours of observations of 18 pet parrots’ behavior over a three-month period.

During the study, the birds learned how to ring bells whenever they wanted to make video calls. When they connected with their favorite bird friends, they danced together, sang together, showed each other their toys, and mirrored each other’s behaviors.

Dr. Rébecca Kleinberger, an assistant professor at Northeastern University, co-authored the paper about the study along with Jen and Dr. Ilyena Hirskyj-Douglas from the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Rébecca says the transatlantic team of researchers remained clear about the goals of the project.

In an article for Northeastern Global News Magazine, she explains: “Can we benefit animal lives, reduce boredom, and make sure we’re not just doing that for entertainment of humans? A lot of the previous work on animals, specifically animal technology, has either been in terms of trying to test or demonstrate animal intelligence, trying to give animal(s) puzzles and understanding how their minds work, trying to learn things for humans, or benefiting humans mainly in some way. From the beginning our focus with Jen has been to put the animal first — to really think about (whether) there is some true benefit.”

Ilyena notes that there are 20 million parrots living in people’s homes across the United States. In a statement about the research, she asks, “If we gave them the opportunity to call other parrots, would they choose to do so? And would the experience benefit the parrots and their caregivers?”

The initial video calls during the study period were limited to a maximum of five minutes. The birds’ caregivers would end the calls as soon as the parrots’ attention drifted. Some birds, though, couldn’t wait to get back on the line. “We had two macaws who were both in their 30s and who hadn’t seen another macaw in decades,” Jen says. “They’d race to call each other first, and as soon as their five-minute calls ended, they’d race back to their bells and call each other again. It was amazing.”

This article was originally published in the January/February 2024 issue of Best Friends magazine. Want more good news? Become a member and get stories like this six times a year.

Let's make every shelter and every community no-kill by 2025

Our goal at Best Friends is to support all animal shelters in the U.S. in reaching no-kill by 2025. No-kill means saving every dog and cat in a shelter who can be saved, accounting for community safety and good quality of life for pets.

Shelter staff can’t do it alone. Saving animals in shelters is everyone’s responsibility, and it takes support and participation from the community. No-kill is possible when we work together thoughtfully, honestly, and collaboratively.